James joined the Playing for Keeps radio show to explore how The Hunger Games and chapter 7 of the Old Testament book of Joshua have something very important in common: a lottery in which the winners get to die for the sake of the community.

A transcript of the podcast recorded by the Raven Foundation.

Adam Ericksen: Hello and welcome to playing for keeps with Bob Koehler, our producer Suzanne Ross who will be monitoring the chat rooms and commenting, and me Adam Ericksen. At playing for keeps we want to engage you in creative thinking on the most pressing subjects of our time, building a lasting sustainable global peace. If you are interested in fostering that kind of peace in your life, and in our world, then we hope you will play for keeps with us. This is serious business, but a world of peace will certainly be a joyful and playful place. So while we’re bringing you our features and interviews with people making a difference for peace we’ll try to do it with a playful touch. Playing for keeps is a project of the Raven Foundation where I am education director. At Raven we offer blogs, arts and entertainment reviews, and events all focused on raising awareness about building a global peace, so please check us out at ravenfoundation.org . My co-host Bob’s an award winning peace journalist who writes a weekly column for his website Common Wonders and is syndicated by certain media services. In his articles Bob diagnoses conflicts and provides authentic paths to peace. Bob is teaching a course at the Chicago’s DePaul University called “Peace Journalism”. Bob, How’s that class going?

Bob Koehler: Well, I’m halfway through, Uh I think it’s going really well. I’ve got 18 kids in the class and some of them are on top of the game and some aren’t, but I’m very excited about it.

A: Well I’m glad that you bought up games, Our guest today is James Alison, priest and theologian. James is actually part of the Raven Foundation family as he is the author of a new course called “The Forgiving Victim” which we at the Raven Foundation are producing. “The Forgiving Victim” is an adult induction into the Christian faith based on the thought of René Girard. You can watch an hour long video of James and the forgiving victim at – forgivingvictim.com And you can also find more of Jame’s work at his website – jamesalison.co.uk . Well, James how are you?

James Alison: I’m very well indeed thank you.

A: Good, thank you for being with us.

J: My pleasure.

A: James is actually in the studio so we’re excited to have him.

B: A first!

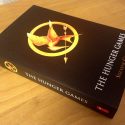

A: Yes a first. Bob beautifully bought up games, and today we would like to talk with James about “The Hunger Games” and also related to the Bible, specifically Joshua Chapter 7. And you’ll see how we do that in a little bit but first… Bob you’ve seen the movie right?

B: Absolutely.

A: And James you saw the movie?

J: Last night

A: Last night, yeah I’ve seen the movie and I’ve read the book too so I might bring in a few things from the book, but first I wanna get your reactions about “The Hunger Games”, James what was your reaction when you were watching it last night?

J: Well it was beautifully made, I had a feeling especially in the first half of being in the presence of something sinister, and then it became clearer to me that it was a kind of high school movie but the nasty version, it was like what I would called the Un-Glee. If Glee is the high school experience from the point of view of the underdog. This was the the high school experience leading to a pretty nasty dénouement, That was my sense.

A: Yeah, yeah… Bob, how did you feel about the movie?

B: Well, I think it was a little more positive than James’ although not with any final conclusion on… you know did I like the movie or not. I did essentially like it in the sense that it was a well made movie, well made, well acted movie and very engaging. And I thought it was an interesting social critique of contemporary society with you know the TV commentator interviewing the participants in the games, it was just so over the top, it felt like an excruciatingly painful over the top version of the TV culture we live in, this reality TV stuff that is getting more and more absurd. So it felt like a critique of that. But I think as we were talking earlier, about what is beyond that, is there a real social statement that the movie wound up making or did they just wind up like so many other movies, having fun with violence, I haven’t decided on that yet, I don’t have a final opinion.

A: One of the things I found interesting about the book and the movie is that I think it points to how cultures of violence use violence in order to attempt to keep the peace or to make peace, um you see this in the Capitol, and a little bit of the history of the country Panem, it’s post apocalyptic America right? And you have the Capitol and you have, what were 13 districts around, and the Capitol tells the history in a very specific way, right? So the 13 districts have this uprising, they rebel against the Capitol, and the way that the Capitol tells this story, is from the perspective, they’re the victors of the battle and they are the ones who get to tell the story, right? The victors get to tell the history of the world. And they tell it through their eyes, and through their eyes, what happens is that the districts all rebelled against the innocent, the good Capitol. And so the Capitol is the one who provided all this food and all of these resources to the district and they rebelled against us!

B:The giving and the nurturing Capitol…

A: Yes, yes… We are the good innocent ones, they are the bad ones, why would they rebel against us? And in order to keep the peace we must get the hunger games and remind them of our history and retell this, what mimetic theory would call this myth, we retell this myth, of we being the good and innocent ones, and they are the bad ones and I begin to question this story because it’s told from the victors point of view. What I think the Hunger Games begins to do, is to tell the story through a different persons eyes, Katniss’ eyes who’s, one could say at the beginning is the victim, it’s seeing the story told through the victims eyes.

And this you begin to see at the reaping, which I think is an interesting way that the capital uses in order to bring home this message.

B: The reaping is just a lie… choose victims…

J: And there is a knowing element about it, and you stress the way in which the Capitol tells its story by means of a film, a propaganda film, and then shows everybody, but there’s a later stage of the movie where the president of the Capitol, does tell his games organizer, how much they in the Capitol depend upon the raw materials to be got from the district, in other words its the subjugated districts that are in fact the ones who are providing…

A: It’s nothing to with real life *laughs..*

J:Yeah *laughs…*

A: So lets get more into this, the reaping, where you have the Capitol who picks two teenagers from the districts, a male and a female, to participate in this Hunger Game which is a basically a sacrifice…

J: To be called “tributes” which is a wonderful term.

A: Yes, they’re to be called “Tributes” and what is the point of the reaping, there’s this randomness where each tribute has their name in this bowl, and they get handed out, and there’s supposed to be this random quality to it, what is the point in this randomness?

B: Well for me the point of the randomness is it creates the illusion of objectivity. And I got that same impression reading the essay by James, is that that is also called God. God is this great removed, objective being, looking down on his creation and maybe playing a little bit with it, but it’s objective. So in other words while it’s random, the randomness indicates God’s choice.

J: God referred to in the film as “The Odds”.

B: Right! “The Odds” Everyone’s favorite! God’s and odds!

J: I think there’s a psychologically important element of the lotteries in which you see in the film, and which is also apparent in the Joshua text, is the way in which is allows for a long slow deliberate build-up which keeps everybody on their toes. Both it’s an object of fascination and an object of dread at the same time. Which in the case of those districts, all the people of a certain age being obliged to put their names in, and it’s being repeated a number of times, so that the odds on them go up, as they get older, with the result that everybody is sucked into belonging to this system, so they’re all in awe of it, they’re all counter to it.

A: You see more of this in the book actually because the capital makes the reaping day into a holiday, everybody gets the day of school, you get the day off work, it’s supposed to be this joyous occasion for everyone, it’s broadcast throughout Panem, everybody wears their greatest clothing on this day, and so everybody gets to see the other districts celebrating this day. I think there’s a mimetic aspect to this, cos when you see other people celebrating this day, it tells you “yes this is something to be celebrated”

J: And you’ve got them to get on board with being more celebratory, so that other people.

B: Well what you’re celebrating is basically life’s existential uncertainty. Because either you if your a teenager, or a loved one will be chosen as the tribute. So it’s a horrible dread that you are in the process of celebrating, but then of course as for most of the people the dread will turn into joy, that neither they nor their loved ones were chosen, which will make indeed a day worth celebrating, except for the two unlucky ones.

A: Yeah as long as your own children don’t get picked there’s something to be celebrated…

J: Except that even if you’re not picked you’re still sucked within the system…

B: Yes, right, the joy is fleeting.

J: Well, it’s fake…

B: Yeah or fake…

J: It’s fake because, underlying it all is a constant terror, and I think in that sense it is a terroristic operation.

A: And it’s a box point, at the end there’s this relief, that you weren’t the ones chosen, there’s this relief that you don’t have to go through this terror.

J: This time, but you’re going to have to live with the consequences of the game forever. And I think that’s one thing which is brought out really well in the film is the way that the previous winner, is he called Haymitch? His only way of coping with his survival of guilt is heavy drinking.

B: Right exactly.

A: Yeah.

J: It was quite chilling, and that’s something which you get in both in the Joshua account, and in the famous American short story “The Lottery” account by Shirley Jackson which is the mixture of the festive and the terrific, the terror-rific. I think that that’s something which is well brought out. I think that that’s a horrendous part of the sacred. This mixture of a certain enforced festivity with a backdrop of a context of terror, and I think they brought that out quite well. I don’t think it’s critiqued, I saw it as how things are.

A: Well lets move into Joshua. James would you be comfortable telling us a bit about the story in Joshua chapter 7 with Joshua and Achan?

J: Yes, well anyone can look it up, it’s quite a short chapter in the bible. It’s the story of how Joshua sorts out a small military problem, because after the siege of Jericho which the people of Israel had successfully besieged, they’re faced with a military problem. Just before the siege of Jericho, God had ordered them not to loot, everything taken in the city was to be put under a ban and devoted which meant consecrated over to God so there would be no looting, no dividing of the spoils, not to the military. An unlikely prospect. But anyhow, so after having besieged Jericho they’re about to go off and conduct the next military operation in a much smaller less significant place. So Joshua sends out scouts to the neighborhood and they report that there aren’t many soldiers there and it’ll be a bit of a cake walk, no great problem. So Joshua can just send a few troops and he’ll wipe out the remaining resistance and take over the area easily. But the scouts were misinformed. They were not up to their intelligence gathering operation. And so when the rather few troops that Joshua sends out come to the place in question, they’re beaten back in a skirmish, it’s a small skirmish. But it has a very great effect on moral because the whole force of Joshua’s army’s trek was their belief in their manifest destiny that they were the chosen people who were going to the promised land and everyone else was supposed to fall into that narrative. And losing in a skirmish, while it might not be militarily very important, its very important for morale because if a big army that’s supposed to be winning, loses in a small skirmish, then who’s to say they might not lose on other occasions. So the people who were going to give up easily say “hey maybe we’re more worth resisting than we had thought”. So Joshua’s army’s faced with a big morale problem, and Joshua himself is faced with “well what do I do about this to restore morale”. In the biblical account he falls on his face before the Lord and says what have we done to deserve this? And God whose role in Joshua chapter 7 is quite simply that of the organizer of a lottery. God does nothing else at all, he says to Joshua “ Rise up – here are the instructions for organizing the lottery, I will point out to you who the skunk is, who’s fault this all is, who’s the red under the bed – you will then sacrifice this person, and we’ll all move on”. Whereupon Joshua does exactly that. But it’s very interesting description, exactly how a lottery works because Israel was divided into 12 tribes and so you actually see the process of the finger pointing, pointing to a smaller and smaller number of people so you’ve got to watch the process of more and more people feeling relieved that it’s not them.

B: Right, the great joy – it’s not me!

J: But also, the realization that the end of this process is a human sacrifice in which they’re all going to be involved so it’s not as though it’s simple relief. It’s rather a complex thing. And then at the end the person at whom the finger points, the person called Achan who’s a person of no great importance. He is called before the tribunal and ordered to fess up, which he does, he fesses up…

B: Or at least the story has him fess up.

J: Right the story has him fess up but then the stories written from the point of the survivors. But he fesses up , he says yes this did happen and immediately soldiers are sent to find hidden treasure under his tent so that it could be proved that he did wrong. And then everyone gathers together and all as one person they stone him to death and they burn everything that he owned. And they not only burn his property so that there’s no property to divide amongst themselves, all his cattle his tents and everything all that is destroyed so there’s not squabbles over remnants. But also all his family are burnt so that there are no surviving witnesses to give another version of the story. So it’s the complete rout of alternative visions of what’s gone on.

B: So the joy of the ones not chosen in the lottery is very much stained with blood. I mean as they feel joy and relief they start to pick up a stone.

J: Well, Yes.

B: That’s quite an association of what joy then becomes.

J: Well yeah, we actually got little hints of that, that awkwardness, in the film. When the kids were in the woods the ones of them who managed to form a band with each other, they actually looked quite happy, but of course that happiness of being together was tinged by the realization that fairly surely they were going to have to kill each other.

B: Yeah right. They can join forces to kill some other people but eventually.

J: The role in the lottery is not – you get to be a victim or your let out of the system altogether. It’s you get to be a victim or you get to be a stone thrower.

B: Right, so the society is sealed in violence.

A: What’s the significance of, you say everyone takes a stone, what’s the significance of everybody needing to be?

J: Because it everybody does it, then nobody does it, no one is responsible. So then, that’s if you like the objectivity that Bob was referring to. Because if everyone has done it then nobody’s responsible. Then of course it was God who did it. And the moment that everybody does it and it works then everyone experiences a moment of peace. And the lottery has had it’s function of bringing everybody together again but restoring morale.

A: So this act of violence that unifies the group over and against another brings a sense of peace.

B: And that becomes the definition of peace then if all was held together by violence…

J: It’s very short term peace of course…

A: Why the short term?

J: Well because there will be another occasion for a quarrel soon enough and very quickly rivalries will break out and the morale will start to collapse and they’ll need to do the whole exercise all over again.

B: Yeah the definition I’ve heard of peace, from the military, point of view is perpetual pre possibility and that’s what peace becomes…

A: Now callers if you have a question for James please press *8, or for Bob or whoever. So one of the questions that’s going through my mind James, well there’s 2 things, let’s start with the big one, if God’s role is basically the one who’s going to search out this person who is going to be sacrificed. That’s not a God that I really want to believe in, this kind of God troubles me, right?

B: I could believe in this God, but I couldn’t love this God.

A: As long as I can be Joshua, and control this God, and make this God not turn against me, I’m happy with that.

B: Yeah Joshua wasn’t part of the lottery.

A: So what are we supposed to do with this image of God that’s in the bible?

J: Well that’s the hundred dollar question isn’t it. Because if we read the text of Joshua as it stands, God is the organiser of a lottery to back up a system that achieves unity by violent death. And of course there have been some ways of interpreting Jesus’ death as that was simply a replay of that, only God needed to sacrifice Jesus for that purpose. I think that the whole insight that Girard has, this is René Girard, has into the New Testament is to show actually how something completely different is going on, exactly the same structure is being shown up from beneath by someone who is not part of it’s game, and this is what Jesus is doing, is saying – Yes, this is how you do things but I’m going to occupy this space so that you can see what you’re doing and you can learn that you may never have to do this again. And that’s going to be the possibility of you all coming together in unity but not over against a victim. Which is of course a difficult challenge. Because it requires a constant learning to stand back from our tendency to run scaredly into unity at the cost of whoever’s easily expendable.

B: Us versus them, the other.

J: That’s right, and I think that’s exactly the reverse of the role of the Hunger Games. This is why at the beginning I refereed to the Hunger Games as the Un-Glee because there’s quite a serious moment at the beginning where the president, President Snow, Donald Sutherland figure says – don’t allow yourself to be fascinated by the underdog – and yet the whole of the Christian understanding is entirely predicated on the truth coming from the underdog. Which I think is why, that’s the best side of the Glee thing, it’s the realisation that actually the really interesting creative material comes from the underdog. So I think it really is a completely different take and a much more crazy and anarchic take because supposing that the truth really is revealed from the underdogs, the people who don’t actually have any interest and stake in the system of power, then whatever new reality they come up with is going to be crazy and anarchic by comparison with the old system, it’s not going to be a way of manipulating the system so as to repeat it’s games – “now we’re on top we can beat them”. I think that was what was ambiguous in the film, wasn’t clear at the end whether Katniss wasn’t just gaming the system rather than undoing it, I’m not sure.

A: Let’s talk about Katniss’ sacrifice, there at the end. Some people have claimed that this is a Christlike moment, that Katniss has…

B: You mean with the two when they decide on mutual suicide…

A: Right, when they’re about to eat the poisonous berries that will Kill them, and the game makers have manipulated the situation. First they tell them that two people can win the hunger games, and then when they’re the last two standing, they change it and say okay now only one of you can win. So here’s a moment where they have to decide what to do, either they kill each other, try to kill each other, one kills the other. Or Katniss comes up with a very clever way of manipulating, of beating them at their own game. Through another act of violence. What’s the difference between this act of sacrifice and the sacrifice that Jesus made? Is there a difference?

J: I mean I think in the film as far as I can see, Katniss is a very clever player of the game. She doesn’t really have a crush on Peeta, Peeta clearly has a crush on her and so Peeta’s desire not to kill her at the end, he doesn’t at all mind dying to let her through. That seems to at least be sincere. It’s not trying to be creative or anything, it’s just a boy with a crush. Whereas I don’t think she has a crush on him, if anything I think she has a crush on the hunk back on the farm.

A: Gale.

J: Um yes, but she’s playing the game including receiving a set instructions. So she’s knowing how to play to an audience, so I that her take on the whole thing is much more knowing and not part of any deeply sincere form of self giving. Though she’s capable of that as was shown at the very beginning when she did step into the role of her sister in the lottery. But by the end of it you just get the impression she knows that she’s up against a tough game and she’s learning how to be the media manipulator of it.

B: Do you think that her willingness to commit suicide was a knowing willingness and a matter of knowing that they would not allow the suicide? I mean that would make it a manipulative action but if she was really planning to commit suicide, wouldn’t that be leaving the game entirely? In other words not manipulative but an act of sacrifice that ended the game, that broke the back of the game?

J: I don’t know whether it broke the back of the game it would clearly have messed up the game but just temporarily. That was gonna be messed up one way or another, as we were shown the organiser of the game had to commit suicide, so he became in a sense the single victim. I agree it wasn’t clear to me from the film. I think this whole idea of creative suicide is a very dangerous one. That’s why I’m not sure that that’s an appropriate analogy for what’s going on in Christ’s death.

A: Yeah, this is the difference, say more about that.

J: Well, it’s a very difficult one, because it’s always clear in the gospels that Jesus does know what he’s doing, he’s in charge of himself. So you get phrases like in St John’s gospel “ I lay down my life and I take it up again”, But on the other hand it’s also quite clear that he’s simply passive, in the hands of others. In other words this is not a Kamikaze mission on one hand. If he’s perfectly aware of where it’s going to go. He’s also perfectly aware that he’s making something of a show, of his self giving up to death, that there is, if you like, a deliberate crazy element to it. Now how we hold those two together is one of the most difficult points in Christian Theology. But I certainly don’t think that Katniss gave us much of an insight into this.

A: One of the things that you stress in the forgiving victim DVD series that’s coming out soon, is the forgiveness that Jesus offers, I mean this is the whole point right, so this I think to me seems to be the main difference between Jesus and Katnisss. Jesus seeks to offer an alternative way of life which is based on forgiveness where Katniss, even in her self sacrifice for her sister which could be very close to Christ, what she ends up doing is sacrificing herself and perpetuating the system of violence, by participating in it. Whereas Jesus completely stops it, at this moment, by offering forgiveness, no retaliation back.

J: Yes, I am a bit uncomfortable, I hope you’ll forgive me, with taking the film as seriously as this. It seems to me that it’s a high school drama, and it ends with a powdered prom queen, and powdered prom king, starting to look increasingly disgustingly like the adults who’ve been their enemies, the over powdered over wigged people who’ve been their enemies in this whole thing, and that we shouldn’t allow it to be much more than that. I hope that’s not a dampener on the thing. I think it’s quite important to stress that otherwise we try to be a little too transcendental.

A: okay, so let’s go back to Joshua 7. Where do you see God in Joshua 7. If YHWH is the one who brings this about, where do we find something of the forgiving victim in Joshua 7?

J: Of course I don’t think we do, just by taking a text by itself. But then of course there is no such thing as taking a Biblical text without an interpretation. So the whole question is not what does the text say but through whose eyes are you reading.

A: Well this is very interesting because as a Protestant I have grown up on sola scriptura and all you need is Joshua Chapter 7 in order to interpret Joshua Chapter 7?

J: Well in that case you’re in trouble!

A: I am in trouble and I need you to get me out of this trap!

B: In other words you have a Holy text and so you look at the Holy text and there’s the answer and there’s no interpretation needed because the answers right there.

J: But you also know that that’s not true.

B: I also know that that’s not true and I…

A: Well this is why I appreciate your work so much, because you’re challenging a lot of where American Christianity is, at any rate, which is basically the Bible says it, I believe it, this is where we’re going. Which leads to I think to a dangerous faith.

J: In the case of this, you can see how if you really take this story, if you use the word the Lord here in the same way, if you apply the word the Lord in Joshua, in the same way as you do in the New Testament to Jesus then you end up with something remarkably schizophrenic. Because here you don’t need to be a genius or wedded to or even opposed to sola scriptura to see that the only function that the Lord conducts in this text is that he organises the lottery. He offers as it were to step in and sort out the morale problem by recreating the unity of the chosen people by indicating to them the victim. If you are to apply the word the Lord literally to the figure in Joshua and the figure in the New Testament then you are left with God deciding to sacrifice Jesus and agree to have Jesus blamed for all the things falsely. The problem that is if we take that seriously, I think that this leads to Atheism and in a sense quite rightly.

B: In other words why do we need a God like this, just forget it, we’re better off on our own.

J: Exactly. This God is a god, in other words, what the Hebrews would regard as a god, someone who is a projection of very easily recognisable social mechanisms. To which we all pray and by which we bamboozle each other. The really interesting, I think the really interesting question is how is it that Jesus blows open the world of the gods and enables us to start to separate out the confusion of how we have confused violence and divinity. So we can start to see that there is no violence in God. All the violence in that is available in the Joshua text is purely anthropological, it’s completely understandable on it’s own terms. You can see the mechanism of the lottery, you can see how it works, there’s no mystical element, there’s no mythical element necessary for it to work, it can work just as easily in a 1st millennium before Christ military operation, and in a 3rd millennium after Christ military operation, or game show. I mean there really is no difference, it’s completely detectable. And in fact that’s one of the things, reading this text now. When I ask people to read this text, I ask them what they would respond at the end if it was in a liturgy. And they all say “Thanks be to God”, and then they giggle awkwardly because they know how awful it sounds to be thanking someone…

B: Yeah for organising a stoning…

J: For organising a stoning, exactly yeah, and thanks to our hostess for our cocktail party and thanks to God for a stoning!

B: And God created the stones we use…

A: So callers just a reminder if you have a question please press *8 and we’ll bring you in on the call with your question.

B: So beyond this text, I mean where is God? In the interpretation, what interpretation do you bring that sees God in here?

J: Well what I think is interesting is if you read this text there is somebody who gets it in the neck. This person is called Achan, and he only makes a very small appearance in the Holy Scriptures, it’s his one and only appearance and he’s quickly in and quickly out and quickly under, because he’s buried under the sand. The interesting thing about this story, who is the figure of Christ. Well is it the Lord? The New Testament Jesus mentions the Lord, very difficult doesn’t seem to be.

B: No, it doesn’t seem like that.

J: Is it Joshua which is after all the same name as Jesus? No it doesn’t seem to be him. Well the obvious figure of Christ is Achan. Why? Because he’s the one who gets it in the neck. And the one thing we all know about Jesus is he was the one who got it in the neck. And I think that what we have in the book of Joshua, this is why I think it’s such a good text, is it sets out the mechanism of to be all against one coming falsely against someone perfectly clearly. And that the New Testament is exactly the reverse of this, you get in the passion narrative exactly the reverse of the Joshua story, but told from Achan’s perspective, the figure of Christ is Achan. So that it’s starting to be opened up and you begin to see what’s going and why what’s going on has nothing to do with God except from the point of view of the shamed one cast out.

A: Great we do have a caller, tell us your first name.

Caller: Hi, yeah Adam it’s Lisa.

A: Lisa, how are you?

Caller: I’m okay thanks.

A: Good, do you have a question?

Caller: I do, I think about this a lot, so in literature and film, it seems as if, and in this case in the Hebrew Bible, the writers, the film-makers see this scapegoating mechanism and see the violence in the world, and yet… I guess my question really is, as a preacher, how do I help Christians to see this, and then not only to see it but take it to the logical point of trying to find a way out of it all.

B: By “it all” you mean out of the violence?

Caller: Right, I mean how do I get the Church’s attention about these matters. I mean it seems like writers of literature and film-makers see it, and people want to see it in those places. They go to… you know Hunger Games had a huge opening but how do we get them to take the next step, do you see what I’m saying?

J: Wow, I wish I could give you an answer! As far as I can see what the process of revelation consists in is God trying to catch our attention to precisely this subject for the last several thousand years. Trying to wean us off our junk identities achieved at the expense of victims so as to enable us to become something more than we are. But the only way to call our attention to this, is not to razzle and dazzle us, in the way that a big liturgy does, a big sacrificial liturgy, or a big lottery like the Hunger Games but by rather quietly occupying the space of shame, the cast out one. Not a very sexy position to occupy.

B: I reduce it to four words, maybe five words. Power with, not power over, tryng to live in relationship with each other rather than in a domination over each other, are we not then beginning to bring the world that you know, Christ wanted, that Christ was creating in his sacrifice or asking for?

A: Lisa, I’m interested in how you would answer your question?

Caller: I don’t know, I mean it’s been a huge frustration to me, that I’ve tried to preach it, and I’ve used every resource I can think of including material from James, and from the Raven Foundation and Michael Hardin, and here I am unemployed now. I don’t know it’s just a frustration. Because to see this, the way that René has kind of opened my eyes, I just expect everybody else to be as amazed by it and as moved by it as I am. And so then I find myself frustrated a lot.

J: I think that you are right. I think that it leads to a lonely path. And I don’t think that that’s accidental I think that that’s integral to the message. There’s that moment in the epistle to the Hebrews where it refers to “now let us join him outside the camp” which suggests that it’s a lonely walk out there, but that that is the creative walk. Uh I agree it’s very frustrating, I’m constantly frustrated.

Caller: Yes, I can Imagine.

B: Frustration is the norm…

J: Well I hope you’re not only frustrated.

Caller: I will say I gave a presentation on Mimetic Theory Wednesday, to a group of clergy, and was really gratified by how interested and willing to hear and enthusiastic they were. So I have moments of hope.

J: Ah, well hope is the key word. Frustration, the word frustra is the Latin for “in vain”. I think that one of the things that we’re doing by following this way of thinking is we’re stepping into apparently the space of vanity, of something in vain, which we can only do if we’re empowered by hope because it means that we’re happy to agree to something that we can’t yet see coming upon us.

Caller: That’s very good, very helpful.

J: The link between frustration which we normally simply use to indicate irritation, but frustration, to frustrate, is to make nothing, to turn vain. But I think the understanding of hope there that you mentioned is very important.

A: Thank you for calling us.

Caller: Thanks.

A: We have a chat room question, Suzanne would you like the read the question. Suzanne: Yeah we do. There’s a question here about interpreting Joshua. “Why can’t we just say that Joshua got it wrong, and leave it at that?”

J: Well I think there’s one sense, in which we are saying that Joshua got it wrong. I think the question is by what authority can any of us say anything at all about Joshua. And the answer to that’s going to entirely depend on the perspective from which you read the story. There would some people who’d want to say Joshua got it right. What you need is to establish a Holy Land with strict boundaries, with in and out, with right and wrong and the way you do this is by sacrificing people.

B: Or you could even pull back from that and say Achan was guilty.

J: Yes, the text will, it clearly says that.

B: Yeah, Achan was guilty, we got rid of him, problem solved.

A: And Achan believed in his own guilt.

J: Yes, that’s right, you could say that, on the face of it, he fessed up. It’s an open and shut case, the Supreme Court would not need to re-open this case.

A: Which is when you have a perfectly run sacrifice when even the victim is willing to accept his or her guilt. Which is also, what I think is the difference between Jesus and Achan, Jesus says “they hate me without cause.”

J: Well he quotes Isaiah doesn’t he, or one of the Psalms…

B: So he doesn’t fess up to his sin against the empire.

J: That’s right, yes, but I think that’s the really difficult thing, is how do we stand, what gives us the authority, to stand quietly, patiently, in the place of shame and to say – this is not the whole story, this is not running the show, this is not what reality is all about, even though it appears to be, even though it has the best tunes even though it appears to win. To refuse to go along with it, you know, like Job in front of his questioners, they all gave him the perfect explanations of why God was doing this that and the other. And he acted like the perfect atheist “no I won’t buy it, no I won’t buy it, no this is wrong.” And then God said at the end “only my servant Job has spoken well of me” In other words the one who was “least godly” I think it’s worth remembering that, that it’s a question of how effectively to protest the system without being in reaction against it and that’s the most difficult thing for any of us to do how to step out of reaction and be creative but without losing the fact that this is a strongly critical activity.

A: We have another Caller. Hello Caller, can you tell us your first name?

Caller: This is Timothy

A: Hi Timothy, welcome to the show, what’s your question?

Caller: Um Kinda like Lisa’s question. Are there novels or popular movies that tell a different story that could open up the imagination. a lot of my folks really were entertained by the Hunger Games and drawn into that but I don’t know that they see the negative side of the story. They just think well that’s how the world is so is there another story that we can tell or read or see.

B: I have one, it’s a short story by Ursula Le Guin called, “The ones who walk away from Omelas”. It is the most haunting short story I’ve ever read. And it describes a utopia, a beautiful society and she goes on for several pages describing how beautiful this world is. And then she says Oh and there’s one more thing. And then she brings us down into this sub basement like a laundry room, and there’s this creature there and you can’t tell … it’s a child but you can’t tell if it’s a boy or a girl, taken away from it’s parents and just left, fed, but otherwise neglected and left in the dark. Somehow this child is part of Omelas as well. That’s essentially the story you know, that at a certain age children are brought to see this child and they’re troubled, and then they go back and they live their lives. Except for a few people who are so troubled that at a certain point in their life they just leave Omelas and they just wander aimlessly cos they don’t know where they’re going. But that’s the story the one’s who walk away from Omelas. It gets that,.. the same thing we’re talking about in a somewhat different way. So that’s one example of the literature dealing with this, in a troubling and creative way.

A: James do you have any suggestions for that?

J: I do but I’m going to be troubled by the language barrier. Because there’s a rather wonderful Brazilian film which actually we saw called “Abril Despedaçado” (“Behind the Sun” is the official English Title) which is the retelling by a Brazilian film-maker of I think it’s a Central European story, a story by Kadare. Essentially it’s about rivalry and vengeance between two near neighbours in a rough part, sort of a frontier part of Brazil’s Northwest, and how each generation needs to take vengeance on the other in order to keep going. So there’s kind of a blood feud going. And how this gets undone, in rather surprising, unexpected ways. But it clearly understands completely how the mechanism of society is kept together by the glue of mutual violence and vengeance, so a horrendous glue, and how someone’s more or less accidental self donation into the middle of that undoes the whole thing. So yes there are examples, alas I wish I could give you the English title, if the film has been released in the English language, but I guess it has, but in Portuguese it’s called “Abril Despedaçado” (“Behind the Sun” is the official English Title) Which literally means April torn to pieces, April unpieced.

A: Suzanne has a suggestion…

S: Well I just have a couple of comments. One is that Adam blogs regularly on pop culture, and TV shows and movies, so if you go to his blog in the beginning you’ll see a whole bunch of critiques of contemporary film and TV shows that might give you some resources. The other thing is that, not to self promote or anything, but there’s a musical, a very popular musical out there called “Wicked” which is very powerful in revealing the scapegoating mechanism and the ways out of it. I am not referring to the Maguire novel I am referring to the Musical by Winnie Holzman and Stephen Schwartz. So if you are interested in stage presentations that’s an excellent musical to look at. And also René Girard has a wonderful volume on Shakespeare. His first book was on European Novelists and so if you want to go to some classic literature like (can’t hear the names sounded like Dostoevsky (maybe – Dostoyevsky) and svendoll) things like that. René Girard’s first book ,“to seek desire in the novel” unpacks all those. His book on Shakespeare, “Theatre of Envy” unpacks all of that drama…

J: And without wishing to cut Suzanne off there, she refereed to the musical “Wicked”, but her own book on the subject of Wicked, “The Wicked Truth”, is to my mind better than the musical in explaining and bringing out the Girardian themes that we’ve been discussing.

S: Right, and in the chat rooms someone says anything by Flannery O’Conner. And The book of Revelation. They also mention Dostoyevsky (I think?!) and Theatre of Envy, so yeah those are fun things.

A: Timothy you asked us, but do you have any examples yourself? Caller: I’m sorry I don’t.

A: No okay, well I hope we’ve been helpful to you and to others

Caller: Yeah that’s fantastic

J: Someone just told me, a close reading of is it called Battlestar Galatica or Battleship Galatica?

S: Battlestar Galactica

J: Battlestar Galactica the series offers a very good take on this.

A: Well Timothy thank you for calling and thanks for listening in.

Caller: Thank you

A: Good to have you! Well it’s coming close to our the end of our hour, do we have any more questions in the chat room?

S: No, not that I can see…

A: No?… Well would you guys like to share any concluding thoughts on the Hunger Games and Joshua 7?

B: Well I guess for me the big question is what comes after the forgiving victim? I mean where are we progressing toward? I mean have we moved beyond what Christ was trying to teach in the New Testament? It seems like it’s been a long hard lesson to absorb by human society. So I guess I leave that as the big unknown. What is the next chapter of humanity’s holy text? Are we in the process of writing it? Is there a world where we have actually put the victim issue r the enemy issue to rest? And then what kind of world is that going to be that we are then creating?

J: I think that the only answer to that is very fragmentary. I think that that’s something that’s part of dwelling in the space that Lisa mentioned of the frustration. Living the apparent “frustra” in hope, is because you only see little signs of this. But the little signs are real, and you do see people turning the other cheek, and giving way, and agreeing to lose so that other people can win. And in surprising circumstances, and in a surprising ways it’s often not related to the official structures of Christian religion, in other words it’s often the people who don’t seem to have a formal purchase on this set of ideas that get it, and while those who do have the formal purchase are very often the last to get it but then that’s been going on ever since the New Testament!

A: There is a modern preoccupation with victims. I think that we’re able to see our victims more and more and you see in Joshua 7 where everybody unites over Achan. You rarely see that any more. You hear more and more voices of people saying “this isn’t right”.

B: But what you also get is an empire like the American empire describing itself as the victim. We were the victims of 9/11, we were the victims of the “terrorist Indians”, that we destroyed, that we were in the process of committing genocide against…

A: …and out of that victimhood we can retaliate, we can seek some kind of revenge…

B: …Yeah, that’s right, so there’s sort of a propaganda backlash that claims the victim for oneself as the dominator.

J: That was one of the things that left me uneasy about the Hunger Games was that in a sense I got the impression that the whole victim thing was being elided out. That it was much more to do with the system and the playing of the game, and that I think was why I began to feel that there’s something sort of Nietzschean going on here, but there’s an eliding out into a world in which innocence, goodness, badness, reality doesn’t really exist – it’s the game…

B: It’s the game!

J: …and I thought that was quite sinister.

A: And for fans of the Hunger Games we know that there are two books left and maybe when the movies come out we’ll discuss them then and we’ll see if they continue that pattern… We just have another question..?

S: We just have a comment from Madrid for James… “Greetings from Antonia Guerra!”

J: Hi Antonio! Good to hear from you, hope all is going very well there!

S: We’ve had some international participation thanks to your reach James!

J: Thanks very much!

A: Excellent well that brings us to the end of our hour, Bob and I would like to thank our guest James Alison for being with us today and you our listeners for tuning into playing for keeps. A reminder that if you want to look more into James his website is – jamesalison.co.uk . And be sure to check out his new course called “The Forgiving Victim” at forgivingvictim.com .You can help us share the word about playing for keeps by following our show on Talkshoe and remember that you can follow Bob at commonwonders.com and me at ravenfoundation.org. We’re very excited for our next episode which is Monday May 21st we will be talking with Kathy Kelly. Kathy has been nominated three times for the Nobel peace prize. She’s an advocate for non-violence on a global scale, she has risked her life by making multiple trips to Iraq and Afghanistan to deliver medicine and toys to children. Kathy has been arrested more than 60 times for her non violent protest, and we look forward to hearing more of Kathy’s story on May 21st. We don’t know the specific time yet, but follow us on Talkshoe and at the Raven Foundation website and you will learn more, until then remember when it comes to peace we are playing for keeps!

Transcribed by Lydia Gibbons